The History Of Prolotherapy Regenerative Medicine

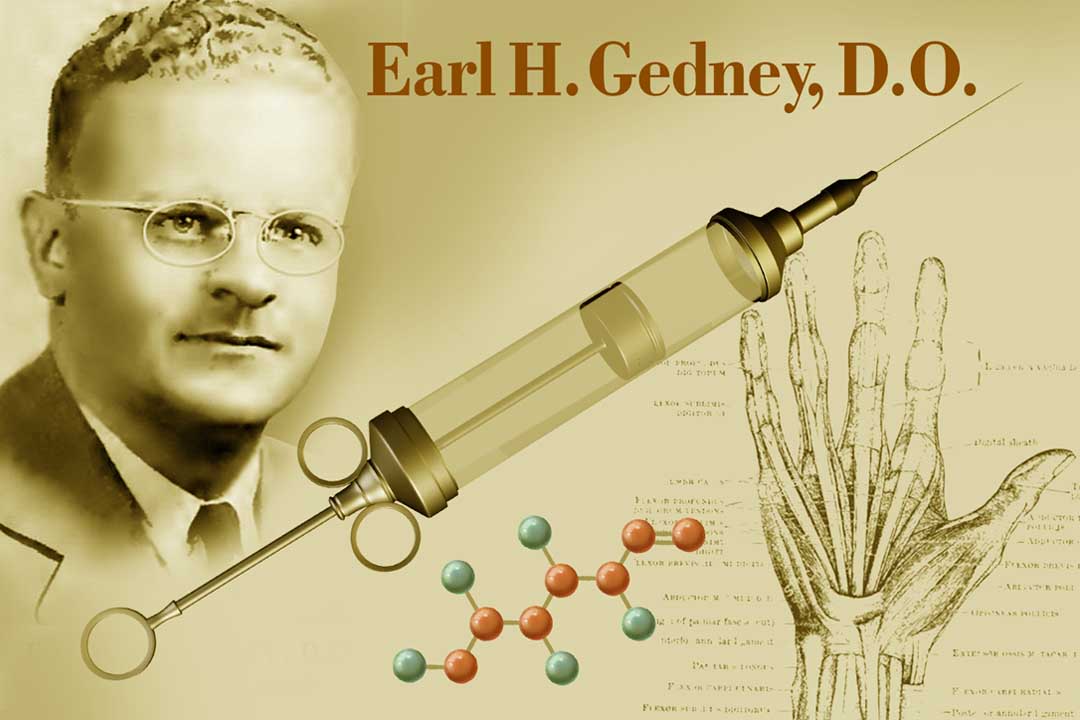

Prolotherapy was born from the work of several forward-thinking physicians, beginning in the 1930’s. The earliest report of its use was around 1936 when Earl Gedney, DO, a general surgeon at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, caught his thumb in closing operating room doors, which badly stretched that joint. After suffering several months of thumb pain and instability, colleagues told him nothing else could be done. He was advised to just “live with it” and to change professions since that injury prevented him from working effectively as a surgeon. However, Gedney was not of the mind-set to agree with this, so he started thinking outside the box and researching other options.

He remembered attending a lecture about using irritating solutions to treat abdominal hernias (A hernia is a muscle tear resulting in an opening or defect). In the 1930s, the risks associated with surgery were high, and so a nonsurgical approach to hernia repair was quite popular. Gedney knew about a group of physicians, called “herniologists”, who had been using a nonsurgical technique for years. The idea behind the herniologists’ treatment was that injections of irritating substances at the hernia muscular opening stimulated repair and the formation of thicker, denser tissue that closed this defect. These irritating solutions were said to cause “sclerosing” (thickening or hardening), and the technique was called “hernia sclerotherapy.” The first organization devoted to hernia repair using this method was formed in 1923, and by the early 1930s, such procedures were widely accepted as very effective in the treatment of hernias.

The Leap to Joint Prolotherapy

Gedney applied this knowledge of nonsurgical hernia repair to the nonsurgical repair of joints, ligaments, and tendons (connective tissue). He concluded that ligament or tendon injury around a joint causes instability, which then results in pain and weakness. He reasoned that if instability could be improved by strengthening the joint connective tissue—similar to what was being done with hernia defects—increased stability and decreased pain would result. Figuring that he had little to lose by being a guinea pig for his own theory, he started injecting his thumb with these irritating solutions. The effect was dramatically successful. Before long, he was back working as a surgeon. Excited about his results, he began a lifelong career of exploring this technique, which he named “joint sclerotherapy.”

In June 1937, Gedney published the first journal article on the topic titled “Special Technique: Hypermobile Joint, a Preliminary Report.” His article included a protocol and two patient treatment reports—one for knee pain and the other for low back pain—both successfully treated with this technique.[1] The next year, Gedney gave a presentation at the meeting of the Osteopathic Clinical Society of Philadelphia, where he outlined the theory of using irritating solutions to heal stretched, painful ligaments, tendons, and joints. He started working with different treatment solutions and perfecting this method with a colleague, David Shuman, DO. Both men began using it in the treatment of unstable joints, especially knees, lumbar spines, and sacroiliac joints. In 1949, Shuman published an article in The Osteopathic Profession titled “Sclerotherapy: Injections May Be Best Way to Restrengthen Ligaments in Case of Slipped Knee Cartilage.”[2] Both Gedney and Shuman continued to do research and publish reports throughout the 1950s and ‘60s. They studied the microscopic effects of various formulas on ligaments and tendons to establish workable protocols for different joint treatment areas. They also traveled to medical centers and physician groups to discuss and demonstrate injections.

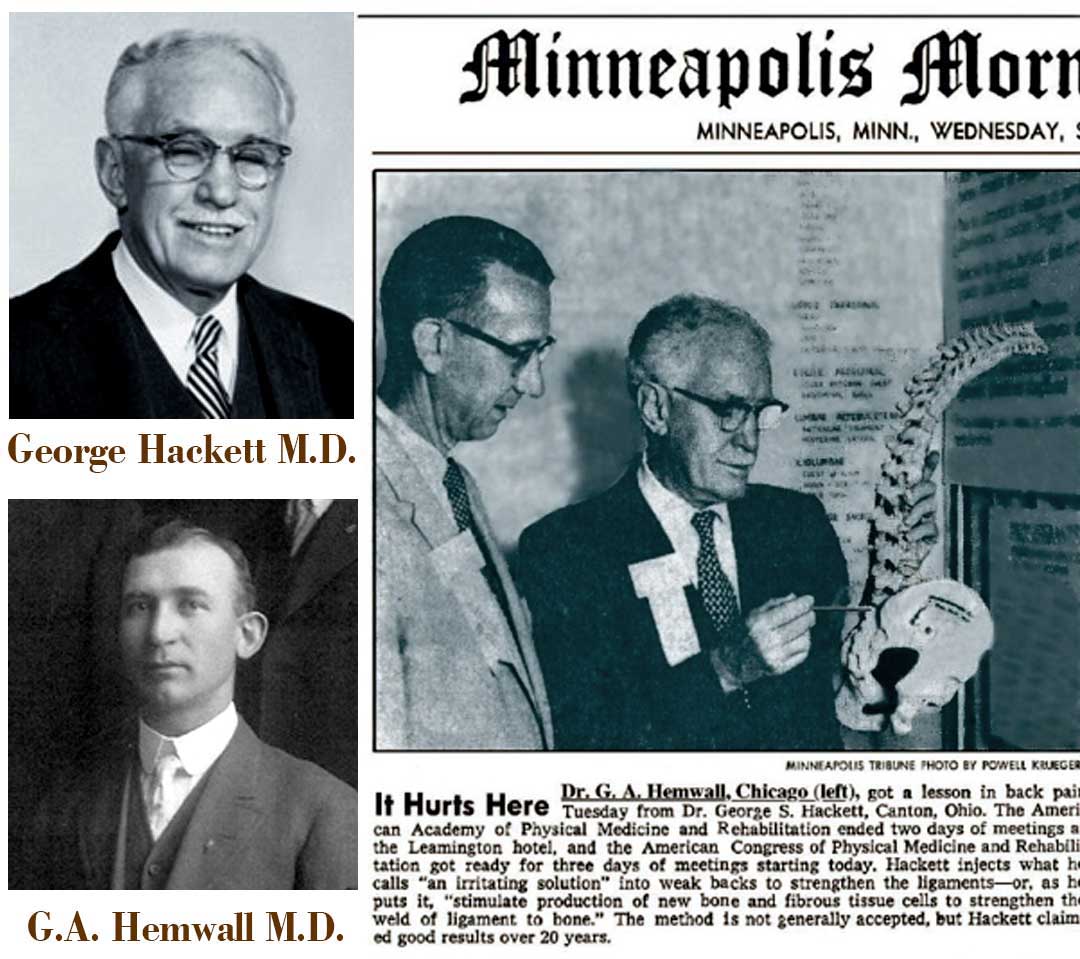

During this same time period, George Hackett, MD, a trauma surgeon, made an interesting observation while performing surgery on patients who had previously received sclerosing treatment for muscular abdominal hernias. When done properly, the sclerosing solutions would have been placed only into the muscular defect; however, sometimes the solution was inadvertently placed deeper, at the junction of the ligament and bone. During his surgeries, Hackett noted this and is quoted as saying, “Injections made (in error) at the junction of ligament and bone resulted in profuse proliferation of new tissue at this union.”[3]

In 1939, after 20 years of patient care, Hackett concluded that low back pain had a strong relationship to weakened (relaxed/stretched) spinal ligaments.[4] He proposed that injections of proliferating solutions could help strengthen weakened ligaments or tendons, and coined the word “prolotherapy,” short for “proliferation therapy” because of the treatment’s ability to stimulate repair and proliferation (growth) of new tissue at joint injury sites. In 1956, he published the first formal physician’s textbook on the subject titled: Ligament and Tendon Relaxation Treated by Prolotherapy. Hackett is also known for the statement, “A joint is only as strong as its weakest ligament.”

Hackett, like other pioneers of Prolotherapy, went on to teach these techniques to fellow physicians, including Gustav Hemwall, a family physician in Illinois. (The two men appear together in the following photograph from the Minneapolis Morning Tribune).

It is interesting that in 1937, an article by another physician, Louis Schwartz, appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association, reporting on the successful treatment of temporomandibular joint instability (TMJ: a joint in the jaw), using a proliferant solution.[5] There is no evidence of direct collaboration between these different groups of doctors, so it would appear that all these physicians arrived at the same conclusion independently: Prolotherapy had the potential to resolve joint instability and pain.

Books directed towards educating the general public started emerging in 1960 when David Shuman published the first layperson’s book on joint Prolotherapy entitled Your Aching Back and What You Can Do About It. Then, in 1990, William Faber, DO, and Morton Walker, DPM, published Pain, Pain, Go Away. In 1998, Ross Hauser, MD, a protégé of Dr. Gustav Hemwall, began publishing multiple books, starting with Prolo Your Pain Away! C. Everett Koop, MD, the former U.S. Surgeon General, wrote the preface to the first edition of that book, indicating:

- “The reason why I consented to write the preface to this book is because I have been a patient who has benefited from Prolotherapy”, and was “remarkably improved to the point where my pain ceased to be a problem…. I was so impressed with what Dr. Hemwall had done for me that on several occasions, just to satisfy my curiosity, I watched him work in his clinic and witnessed the unbelievable variety of musculoskeletal problems he was able to treat successfully. Many of his patients were people who had been treated for years by all sorts of methods, including major surgery, some of which had left them worse off than they were before…. Yet I saw so many of them cured that I could not help but become a ‘believer’ in Prolotherapy.” He went on to explain “I was so impressed with what Prolotherapy could do for musculoskeletal disease that I, at one time, thought that might be the way I would spend my years after formal retirement from the University of Pennsylvania. But the call of President Reagan to be Surgeon General of the United States interrupted any such plans.” [6]

Physician Education

Formal, large-scale physician education began in 1954 with the creation of the American Osteopathic College of Sclerotherapy. In 1956, this group became recognized and chartered by the American Osteopathic Association (AOA), and offered the first official training for Prolotherapy techniques. This AOA affiliate group is known today as the American Osteopathic Association of Prolotherapy Regenerative Medicine (AOAPRM). Other groups, such as the Hackett Hemwall Patterson Foundation and the American Association of Orthopedic Medicine (AAOM), also continue to educate physicians in traditional as well as newer forms of Prolotherapy. The collective knowledge of over 80 years of outside the box, creative thinking in how to stimulate healing has resulted in modern day Prolotherapy Regenerative Medicine.

Bibliography

[1] Gedney E. Special technic: hypermobile joint: A preliminary report. The Osteopathic Profession. 1937; 4(9): 30–31.

[2] Shuman D. Sclerotherapy–injections may be best way to restrengthen ligaments in case of slipped knee cartilage. The Osteopathic Profession. 1949 March; 16(6): 18–19.

[3] Pomeroy KL. Sclerotherapy, prolotherapy and orthopedic medicine: A historical review. Presented at the American College of Osteopathic Schlerotherapeutic Pain Management seminar, 2002.

[4] Hauser RA, Hauser MA. Prolo Your Pain Away, 3rd Edition, Caring Medical and Rehabilitation, Oak Park, Illinois, 2004.

[5] Schultz LW. A treatment for subluxation of the temporomandibular joint. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1937 September 25; 109(13): 1032–1035.

[6] C. Everett Koop, Preface. In Hauser, Prolo Your Pain Away, 1st Edition. Oak Park, Illinois: Beulah Land Press, 1998.